Dalit capitalism, the new mantra to move up the social ladder through economical enterprise

29-September-2012

Vol 3 | Issue 39

To be a true follower of Ambedkar, become a 'job-giver' not a 'job-seeker'. Do not fight capitalists but try to become one amongst them.

-- Milind Kamble, of the Dalit India Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI) in an interview on CNN-IBN

An inaugural function of a different kind was held at the end of August 2012. Around 150 aspiring dalit entrepreneurs clad in suits gathered in a star hotel in Bangalore. They were there to inaugurate the Karnataka chapter of the Dalit India Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI), a national body formed to promote dalit entrepreneurship as a solution to the historic socio-economic problems faced by dalits.

|

|

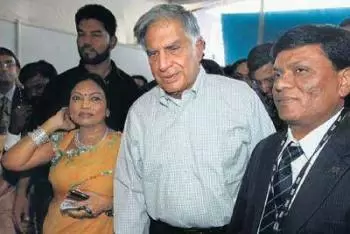

Ratan Tata with Milind Kamble, Chairman, Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (DICCI) (Photo: Infochange News and Features)

|

Milind Kamble, a successful entrepreneur himself and a key figure in this formation, told the gathering how the organisation had expanded; it now has a presence in 18 states with 2,500 entrepreneurs whose combined annual turnover exceeds Rs 20,000 crore. According to him, this emergent 'dalit capitalism' would act as a powerful tool to fight caste-based discrimination.

This was definitely not the first time the nascent emergence of dalit capitalists has made the headlines. In fact, dalit people's foray into the arena of capitalism -- defying Manu's dictum -- has become the latest talking point. (Manu here refers to the age-old text Manusmriti signifying the textual tradition of Hinduism.)

For proponents of dalit capitalism, the idea is "full of promise" and a "compelling need for the future of India". Indeed, a critical element in "de-segregating Indian society". To confront the "illegitimate dominance of the caste Hindu order", dalits need to create a middle class based on education/white collar jobs/professions. The booming small-scale industry presents an opportunity for the dalit middle class to grow into an economic and social force to be reckoned with.

The whole idea and its likely implementation would be a revolution of sorts in the ethos perpetuated by Manu dharma which prohibits dalits from becoming employers of non-dalits, or making money. For an outsider, the logic certainly looks attractive.

If millions of dalits become entrepreneurs, then thousands will metamorphose into big-time capitalists. This way they can chase away Manu dharma. It must be stressed that without support from society and the state it would be impossible to achieve this.

How should one look at the nascent emergence of dalit capital/capitalism?

One thing that needs to be emphasised at the outset, before one goes into the details, is that this trend has definitely challenged the age-old Manu-led order that relegated shudras/atishudras to demeaning/humiliating professions and forbade them from indulging in economic activity.

Under the varna system, while the four varnas -- brahmins, kshatriyas, vaishyas and shudras -- each had their tasks cut out, the atishudras -- dalits and tribals -- were considered outside the system. No one therefore can deny the democratising potential where the dominance of a few castes/communities over economic affairs is challenged.

Just as the ascendance of Kanshi Ram signalled the growing assertion of dalits in political power (contrary to the fractious Republican politics which limited its role to a 'guest actor' in bourgeois politics), dalit capitalism signals the assertion of dalits for a share in economic power. It is worth noting here that apart from a few write-ups and commentaries, this new turn in the dalit movement has not received the attention it deserves.

Will dalit capitalism really have an emancipatory impact on the dalit psyche? Or will it be just another way to co-opt dalits into the system? The problem arises when dalit ideologues start claiming that it is the way forward for dalits.

Chandrabhan Prasad, a key ideologue of dalit capitalism, says: "A few dalits as billionaires, a few hundred as multi-millionaires and a few thousands as millionaires would democratise and de-Indianise capitalism. A few dozen dalits as market speculators, a few dalit-owned corporations traded on stock exchanges, a few dalits with private jets, and a few of them with golf caps would make democratic capitalism loveable." (Quoted in Power and Contestation, Menon and Nigam, Page 96, Orient Longman)

Will it? Or will some dalit billionaires find space in the Fortune 500 or Forbes 500 list, leaving the broad masses of dalits in destitution without any semblance of security? Can it be said that it is the step needed for the post-Ambedkarite movement to break the chains of servitude and usher dalits into the much cherished 'economic democracy'?

Should one see this as an extension of the emancipatory project launched by Dr Ambedkar, or its exact opposite, leading to further co-option of the radical potential inherent in the dalit movement?

How does one compare the recent experience of dalit capitalism with that of black capitalism? Does capitalism with an adjective -- Black, Hispanic, Dalit, White -- have any import for the situation on the ground? Is 'black capitalism' or 'dalit capitalism' more 'bearable' to the 'black' or 'dalit' toiling masses?

The absence of any critical engagement either from various shades of the Left or from those bred in rich Ambedkarite praxis has created a situation where the ideologues of this 'new turn' are able to present themselves as the real/true inheritors of Ambedkarite legacy. A new-look Ambedkar is being presented before us, more amenable to this new phase in the dalit movement.

Looking back, one sees that the first signs of this new trend emerged in 2002 when the 'dalit agenda' for the coming century was presented and ratified at a conference held in Bhopal.

Modelling itself on the 'diversity' principle of the US and other advanced countries, it talked of adopting a similar model in public institutions and private industry/corporate houses, implementing supplier/dealership diversity in government and private organisations, providing free education to every scheduled caste/scheduled tribe child who came from a low-income household, and starting a system of collective punishment in case of atrocities against SC/STs, as the oppressors enjoy community support and protection from the law.

It also talked of globalisation -- the new modus operandi of capitalism -- as an era of increased opportunities for people, a period of enhanced freedom.

The concept of 'supplier diversity' first made its appearance when the state government announced that the state social welfare department would procure 30% of all goods and services it was buying from the open market from dalit/adivasi entrepreneurs.

A decade later, the debate has been carried forward a step; indeed, today there is talk that dalits have finally 'arrived'. As things unfold before our eyes, we see that the idea has caught on and has been adopted at the Centre.

Why does the concept of dalit capitalism that ushers us into what is being called 'economic democracy' not only sound utopian but also exhibit a very misplaced confidence in "capitalism's potential for social transformation" (D Shyambabu, Defying Manu: Rise of the Dalit Capitalist, January 30, 2011)? Why is it unlikely that the "dalit capitalist will be an effective catalyst in ending (the) community's bondage"?

Numerous examples illustrate the longevity of caste despite tremendous material progress. Surinder Jodhka's paper, 'Dalits in Business: Self-Employed Scheduled Castes in Northwest India'(IIDS, 2010), which focuses on two cities in north India, illustrates how despite an upswing in the market economy helping break a number of barriers, dalit entrepreneurs still face many hurdles.

In an interview with a newspaper, Dr Jodhka, a professor at the Centre for the Study of Social Systems at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, explained: "Most dalit entrepreneurs face problems varying from difficulties in getting enough supplies on credit, lack of social networks, absence of kin groups in the business, and control of traditionally dominant business-caste groups. These, along with other social variables such as lack of social capital, make the dalit situation in India more complicated and vulnerable to homogeneous categorisation."

Another problem is that it helps present a caste-neutral, sanitised version of Indian 'captains of industry', who, as is well documented, have consistently refused to accommodate the rising aspirations of dalits and tribals, let alone play a proactive role in their struggle for equity.

While they have no qualms about acquiring subsidies and other benefits from the government, they have proved slow to execute even a symbolic corporate social responsibility, never mind a special concern for the deprived and challenged. There have even been occasions when they have exhibited their disdain for members of the deprived castes.

A joint study done a few years ago by Princeton University, USA, and the Indian Institute of Dalit Studies demonstrated empirically the deep-rooted caste bias that inhabits the minds of corporate honchos (www.rediff.com, December 4, 2007).

Using a methodology similar to measuring discrimination faced by blacks and Hispanics, it sent around 5,000 applications to leading private companies in India, for 548 posts. While the qualifications in most of the cases appeared similar, the names of a few applicants clearly showed they belonged to dalit communities. The leading companies contacted only those candidates whose names sounded upper-caste. All those whose names appeared to belong to dalits were not even called for an interview.

The Economic and Political Weekly carried an extensive write-up on this. It was ironical that while corporate bosses consistently refuse to offer reservations in employment and talk about giving preference to merit, this study, clearly exposing their caste bias, did not generate any discussion.

Celebration of dalit capitalism also tends to hide the predicament of 'black capitalism' in the US. Before discussing this it would be opportune to compare the situation in India and the US as far as socially oppressed sections is concerned.

Dalits, who constitute around 16% of India's population and blacks/ African-Americans, who are around 13% of the population of the US, share many commonalities as far as social dynamics is concerned.

With the adoption of independent India's Constitution, 'untouchability' -- the dehumanising tradition which had social/divine sanction and which condemned dalits to a sub-human existence -- was outlawed and policies of 'positive discrimination' to ameliorate their plight taken up (1950). It was another 13 years before the US took its first steps in the direction of affirmative action for blacks.

If the emergence of the Black Panthers -- an African-American revolutionary leftist organisation (1966) that achieved national and international recognition through its involvement in the Black Power movement and US politics of the 1960s and 1970s -- signalled a new militant turn in black politics in the US, the rise of the Dalit Panthers (inspired by the Black Panthers) can be said to be a militant phase in dalit politics, which similarly helped awaken the dalit masses from the deep slumber of the post-Ambedkar period.

Today, as we witness the debate around emergent dalit capitalism in India we see that the US has already debated the issue of building wealth through ownership and development of business. Indeed, the debate continues.

The reality of the emergence of black capitalism and its impact on the rest of African-American society is becoming more and more evident every day. In fact, we know for sure the role played by the US government then in nurturing this 'baby of black capitalism' as a countervailing force to the growing radicalisation of the black movement.

It viewed the uncontrolled Black Power movement as a major threat to the internal security of the US (during the '60s and '70s). It was during Nixon's time that the black capitalism initiative as a domestic version of the widely publicised foreign policy initiative of détente (to contain the USSR and China) was formulated. There is enough evidence to show that black capitalism helped achieve the larger ideological goal of subverting African-American radicalism, although it could not achieve Nixon's institutional goals related to black capitalism.

Nixon declared in a 1968 speech: "[W]hat most of the militants are asking is not separation, but to be included in -- not as supplicants, but as owners, as entrepreneurs -- a share of the wealth and a piece of the action."

Federal government programmes, Nixon said, should "be oriented toward more black ownership, for from this can flow the rest -- black pride, black jobs, black opportunity and, yes, black power". ('The Black Power Era', Alan Maas, socialistworker.org)

How does one define capitalism?

The world 'capitalism' is defined variously in different sources. According to the Merriam Webster dictionary, it is '…an economic system characterised by private or corporate ownership of capital goods, by investments that are determined by private decision, and by prices, production, and the distribution of goods that are determined mainly by competition in a free market'.

What is capitalism according to Marxism? For Marxists, capitalism is a system which is based on the extraction of what is known as surplus value. In capitalism, the motive for producing goods and services is to sell them for a profit, not to satisfy people's needs.

Capitalists live off the profits they obtain from exploiting the working class whilst reinvesting some of their profits for the further accumulation of wealth. It is a system under which '(th)e means for producing and distributing goods (the land, factories, technology, transport system, etc) are owned by a small minority of people (the capitalist class).

The majority of people -- working class -- must sell their ability to work in return for a wage or salary. The working class are paid to produce goods and services which are then sold for a profit'.

What would happen if the owners of capital are people of colour? Would they be managing capital differently, apart from the fact that they might be more keen to have a diverse workforce? Would it impact the end result in any significant way? Definitely not.

Let us take another case.

If one substitutes a Ratan Tata with, say, a Milind Kamble, would the story be different on the ground apart from the fact that many oppressed amongst the working class may feel a greater closeness towards a person who leads/owns the exploitative machinery?

The point I am making here is that capitalism is a many-coloured system where the inner core of the system remains the same.

According to Chandrabhan Prasad: "The government ought to constitute a body, say the National Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes Supplier Development Council, which should identify dalit/tribal entrepreneurs who are already supplying goods and services to the government through middlemen, and connect them directly to procurement departments.'

He cites examples from the US where a national body connects minority entrepreneurs with large American firms. When he is asked how it is that on the one hand you sing paeans to the spirit of a free market and yet have no qualms about demanding protection from the government, Prasad argues that the Indian bourgeoisie itself would not have thrived without state support and protection till 1991.

"Dalit businesses, particularly, need help since most of these are small-scale operations," he explains.

Although the contradiction between what is preached and what is demanded is apparent, advocates of dalit capitalism do not seem to be bothered about such inconsistencies. There is little doubt that their espousal of the cause of globalisation or their unquestioned support for capitalism a la the new opportunities offered by economic reforms since 1991 and their potential for social transformation has come at a time when the toiling masses in this country are getting their act together to fight the growing dispossession of people and increasing attacks on hard-earned rights.

Their understanding that the tenets of the market and Manusmriti cannot co-exist shows their ignorance about the Indian social situation. Consider this statement by D Shyambabu, a scholar who is part of the think-tank that helped the idea of dalit capitalism gain wider currency: "Dalit capitalism today is akin to the origins of a mighty river. The spirit of adventure will find its own course, the journey will take a long time and it will be turbulent. What is certain is this -- the dalit capitalist will be an effective catalyst in ending the community's mental bondage, the belief that they are inferior, their plight is linked to birth, and that the government alone can raise them up." (Defying Manu: Rise of the Dalit Capitalist, D Shyambabu, January 30, 2011)

It's true that since proponents of dalit capitalism serve a wider political purpose and are also able to provide legitimacy to the tottering regime, the powers-that-be will continue to extend a helping hand to them at all levels.

"The sky-piercing slogan shouting 'Down with Imperialism' naturally ignores brahminism because of which imperialism could entrench itself in India. The young leaders (refers to the leadership of the Bombay Regional Youth Conference which took place in Pune) do not seem to understand how easy it would be to destroy imperialism if the foundation of brahminism on which the superstructure of imperialism is erected, is itself weakened.

“The power and strength of imperialism lies in the weakness of the classes that are ruled by imperialism. The weakness of India is accumulated in the social structure of the Hindus. Our social norms and traditions are destructive of unity and supportive of division. That is why imperialism could strengthen its base here and it is still able to carry on." -- Dr Ambedkar

In 1967, at Riverside Church, Rev Martin Luther King Jr delivered the sermon and speech 'Beyond Vietnam: Time to Break Silence' and addressed three of America's demons: racism, materialism and militarism. He called the US government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today," and said "the war in Vietnam is but a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit".

He also knew that the only hope for real change "…lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world declaring eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism… The choice is ours, and though we might prefer it otherwise we must choose in this crucial moment of human history".

Interestingly, two great leaders of the oppressed in the 20th century shared a similar fate after their death. If today, Martin Luther King is revered by every US president and the establishment has seen to it that a sanitised image of the man is presented, Dr Ambedkar, legendary leader of the oppressed and the exploited who talked about two enemies of the dalits, namely brahminism and capitalism, is similarly being mythologised by emptying him of his meaning.

It is a tragedy that Ambedkar -- the eternal revolutionary -- who always thought about the emancipation of dalits in the broadest possible terms, who started off his political journey with the formation of the Independent Labour Party and formed the Republican Party of India at the fag end of his life, who fought casteist trends within the movement he led and underlined the difference between Marxism/Socialism as an idea of liberation of humankind and the mechanical manner in which it was implemented here, is today being used by different factions of the dalit movement to buttress their politics.

While his name has been routinely used to explain away all their opportunistic moves to grab political power, today when a section of dalits is keen that their corporate dreams take wing, his name is again being invoked. Setting aside his anti-capitalist content, they want us to believe that had he been alive he would have been a strong defender of their joining the capitalist mainstream.

(Subhash Gatade is a social activist, translator and writer whose writings appear regularly in Hindi and English publications and occasionally in Urdu publications. He edits a Hindi journal Sandhan)

By arrangement with Infochange News & Features