While boys of his age went to play after school, he taught children of his age

18-July-2016

Vol 7 | Issue 29

A 23-year-old young man, Babar Ali, from a village in West Bengal has taught more than 3,000 children in the last 14 years in a school he started when he was only nine.

At a time when his peers are still studying or looking for jobs, Babar Ali already holds a unique post –as head of a school he started more than a decade ago in his village, Gangpur, in Murshidabad district of West Bengal, around 180 kilometres from the State capital.

|

|

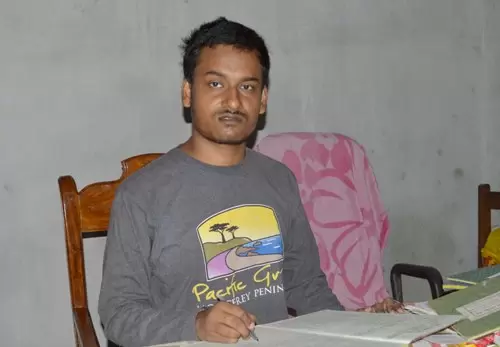

At 23, Babar Ali has already served 14 years as a school headmaster (Photos: Monirul Islam Mullick)

|

Babar Ali is not only the headmaster here, but is hailed as the youngest one in the world. His motto is to fight poverty through education, but his has not been without its problems, including allegations of proselytism.

“I have earned praise for my work across the globe,” he says, sitting in his newly constructed office at Gangpur, “but my journey has been a tough one with people from my village and the neighborhood accusing me of trying to convert children to another religion.”

Babar has not let them destroy his spirit and broadminded vision. After all, he has been an ardent follower of Swami Vivekananda and his teachings since childhood and a regular visitor to the ashram of the Ramakrishna Mission, just three kilometres from his house.

“I used to visit the ashram regularly, with my friends, when we were five or six years old,” he recalls. “We hardly knew about the mission and its teachings, but the deer running inside the park and the fish in the aquarium attracted us. Slowly, I began to get inspired by the teachings of Swami Vivekananda and his selfless service to humanity. I still go there whenever I find time.”

His regular visits to the ashram were not appreciated by his neighbours who warned his parents that their son was moving to another ideology. “Thankfully, my parents too believed in humanity as the true religion,” says Babar.

|

|

Babar's father wants him to become an IAS or IPS officer and serve society

|

The roots of his learning tree lie in his own life. Babar Ali was born in 1993 in the minority-community dominated village of Gangpur. The eldest of four siblings, in 1998 Babar was admitted to the Bhabta Rasidiya Primary School, two kilometres from his house, where he studied up to Class 4.

In 2002, when he was nine, his father Mohammad Nasiruddin, a small-time jute trader with a small income, got him admitted into the Beldanga CRGS High School, about 10 kilometres away. But Babar had to catch the bus first to go there and it was two kilometres from his house to the bus stand.

It was a walk that changed the direction of his life. “While returning from school, I saw children playing in the fields and wasting time grazing cattle,” he says. “I would ask them playfully if they would study if I taught them. They always said yes.”

And Babar took their response seriously. On 19 October 2002, Babar started his classes with eight children including his younger sister Amina Khatun, under a guava tree in the front yard of their one-room house.

“We had a tin roof in the front yard in the name of school,” Babar says. “The whole area used to get muddy during heavy showers.”

He was the only teacher, all of nine years old, teaching children between the ages of five and nine. Babar fashioned a blackboard from terracotta tiles and read out from newspapers before his father contributed Rs.600 for buying some text and notebooks.

|

|

Babar with his father Mohammad Nasiruddin

|

Later, Sanath Kar, the principal of the nearby Beldanga SRF College and a close friend of Babar’s father also contributed books for the school. Kar also formally inaugurated Babar’s school in March 2003, naming it Ananda Shiksha Niketan (House of Happy Learning).

The villagers, who had earlier been skeptical about sending their children to his school, changed their minds after the media covered Babar and his work. Over the next 13 years, the number of students swelled to 800. The Bengali-medium school, recognized (but unaided) by West Bengal Board of Secondary Education in 2012, offered education from Class 1 to Class VIII.

“While boys of my age went to play, I taught children my age from 4 to 6 pm after returning from school,” he says. “Whatever I learned in school I repeated in my class and acted like their headmaster!”

Babar hails 2005 as the most memorable year of his life when as a Class VIII student, he was invited by Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen to Shantiniketan, the prestigious centre of learning founded by Rabindranath Tagore, to speak about his school. In later years, Babar travelled to Europe and Singapore to deliver many such speeches.

|

|

A woman staff striking the gong to announce the end of a class period

|

Recently, Babar has shifted his school to Shankarpara village, three kilometres away from the previous school. Babar had purchased around 7,200 square feet of land there at a price of rupees ten lakh, donated by one of his supporters Ms Almitra Patel in 2013. The newly built school was inaugurated on November 2015.

“Shankarpara is a remote village with no school in the vicinity,” explains Babar. “We already have 300 students including 200 girls, fewer than at our previous address where we had 800 students. We are trying to bring some of those students here by school buses.”

The school has ten staff members including eight teachers. Six of the students who studied in his earlier school have been appointed as teachers. A seven-member committee comprising village elders and retired teachers looks after the administration of the school.

In 2012 Babar was featured in Aamir Khan’s popular TV show Satyameva Jayate. He became a Ted Fellow, talking about his school at the Ted Talks in Mysore, Karnataka.

Babar’s biography was included in the Central Board of Secondary Education syllabus for Class 10, and by the Karnataka government in the Class 12 English textbook.

The school is expanding too and when Babar is away, his sister Amina Khatun, one of his first eight students, is in charge. “We expect to extend our classes up to Class 10 by next year after State Government affiliation,” Babar says.

|

|

The school building was constructed last year in a 7,200 sq ft property donated by an NRI

|

Books, recommended by the School Education Department, Government of West Bengal,are now being provided by the District Inspector of Schools.

“We also plan to start vocational courses for students to help them become self-reliant,” says Babar, “as most of them are taken out of schools by poor parents, who send them to work in distant states.”

Money is a constant constraint and the State government has not extended any financial support. He receives donations from well-wishers and spends around rupees five lakh in running the school every year. But he laments that the amount is not enough.

Babar himself completed English honours from Krishnath College in Berhampore in 2013 and enrolled himself for his Masters in Arts at the Kalyani University, which he is completing by distance learning. His father wants him to become an IPS or IAS officer.

“I will take the UPSC exams to fulfill my father’s dream, but my own dream is to teach children till my last breath,” Babar says. “I want to see each and every child educated.”