The iron lady from Manipur was as strong as this even when she was going to school

08-February-2016

Vol 7 | Issue 6

Irom Sharmila is Manipur’s face of courage and tolerance. Over the last 15 years that she has been on a fast demanding the repeal of the controversial Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), which she says has brought “immense hardship” to her people, a lot has been written about her cause, her struggle and her inspiring non-violent protest.

She has been in and out of protective custody, is being fed through a nasal tube and has to routinely make appearances in court to fight her case but absolutely nothing has deterred her from her mission: to ensure a conflict-free, safe and just environment for the women and children of her state.

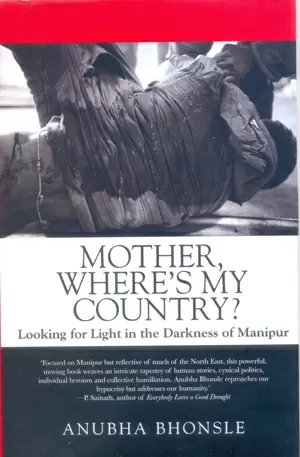

In this excerpt from Mother, Where’s My Country: Looking for Light in the Darkness of Manipur by Anubha Bhonsle, published by Speaking Tiger, catch a rare glimpse of Sharmila’s school days for a deeper understanding of her staunch beliefs and empathetic mindset.

|

|

For 15 years now Irom Sharmila has been making a silent appeal for the withdrawal of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) from her state Manipur (Photo: Tripti Nath\WFS)

|

As children, Sharmila and her brothers and sisters were not sent to the government school nearby. Their father insisted that they walk about two kilometres every day to another school, which had better teachers. Sharmila’s first memory of school is of pointlessness. She did not take to books nor was she a crammer. Wearing a red-and-white uniform with tie and white canvas shoes they trekked to school every morning. Here they would participate in every ceremony the school mandated—on 26th January, 15th August, 14th November. If students missed any of these, marks would be cut. There would also be early morning march past practice, even in the winter cold when the students hated it the most, but they soldiered on, their hands colliding when they sometimes missed a step or fell out of rhythm with the rest. Sharmila participated in all of this, though marbles or hide-and-seek made more sense then.

Once, en route to school, Sharmila threw a tantrum and refused to go ahead. She sat at the foot of a banyan tree and started crying. Cajoling and scolding by elder brothers and sisters made no difference. Tired, they left her and went to school. Eight hours later, when they returned, Sharmila was still sitting there. Years later, when after many requests Sharmila didn’t budge from her decision to fast against AFSPA, Singhajit would recall this incident.

‘It was always hard to get her to change her mind. When she was younger, she didn’t complete her school. She studied only till Class XI, all she said was, “I know how to read and write. I don’t need a degree.” That was it, no one could argue. She wanted to learn shorthand, she said, and she did. We had to agree.’

She wasn’t a big girl, she’d never been in a fight, she avoided confrontation, or even complaint for that matter. She never seemed heroic, she wasn’t good at sports and not much could be said about her grades. She was just Sharmila, lanky, perhaps a little boyish, and inclined to be just herself and by herself. The one time Sharmila dressed up in finery and wore jewellery and make up, she surprised everyone. Her closest friend Romita, almost a sister, was getting married to a young man who worked in the accounts department of a private firm. Part of the same Irom clan, Romita and Sharmila lived two houses away from each other. They would spend many an afternoon together.

|

Dressed in skirts and blouses they would cycle on the streets, look around at the loveliness of the trees or a bird in flight or simply sit in their courtyards and talk, eating fruit or singju, a type of salad made with finely chopped banana stem, laphu tharo or banana flower, cabbage, lotus stem and komprek, a scented herb. It was a special bond. Sharmila had visited Romita in her husband’s house during her pregnancy, gifting her two eggs laid by her hen. It was a sudden visit. Romita’s marital home was far away. Sharmila had complained of the bad roads and stayed back for lunch. A vegetarian dish of cabbage was prepared specially for her. Months later, their lives intersected again when Romita gave birth to a baby girl on the 5th of November

2000, just as Sharmila began her fast. Romita would often tend to her baby and listen to the radio hoping to catch any news related to her friend and her fast. She and her husband would talk about Sharmila, they understood the magnitude of what she had undertaken but Romita now recognized the stillness that was a part of her friend’s being, the unnaturalness of her personality, as if there was a mist, a veil that separated her from everyone.

Descriptions of Sharmila rarely venture beyond her fast, her unique feeding form and her resilient spirit. To describe her solely like this would be to not get her at all. Here was a woman infinitely comfortable in her own skin; comfortable with her tapering fingers that ended in long, broken nails, the delicate slope of her shoulders, her bony cheeks, unkempt hair, her black-brown eyes, pale skin, sensual mouth. Without the nasal tube and behind the strong profile in photographs, she was an ordinary person, sensitive, easily hurt. Beneath her physical confidence there was a layer of timidity, shyness, a childlike impatience, even despair.

Sharmila, would sometimes remove the tube attached to her nose, turn on her side and read. Or simply mumble and moan in a slow halting voice, a voice that rarely betrayed any sense of urgency or discomfort. Simple movements would be difficult sometimes, but even the physical pain, some believe, had almost vanished. Or maybe it hadn’t, it was sitting in some dark corner like a cobweb. Most people had just stopped seeing it, because they had stopped seeing Sharmila as one of them. Heroes don’t hurt. ‘How painful it must be to live like this. I think it’s her sacrifice for all the mothers who fed her milk,’ Sakhi would say.

Sakhi had not sat by her youngest child for years, to ask her how she felt, to comfort her, caress her forehead. Only once, after Sharmila’s return from Delhi in 2006, mother and daughter had come face to face, but not quite. Sakhi was unwell and had been admitted to the same hospital as Sharmila. The daughter, unable to hold herself back, thinking that her mother was dying, had tiptoed into her room at night. Sakhi was sleeping. They didn’t exchange a word.

(Excerpted from Mother, Where’s My Country: Looking for Light in the Darkness of Manipur by Anubha Bhonsle; Published by Speaking Tiger; Pp: 250; Price: Rs 499/Hardcover.) - Women's Feature Service