'Iron lady' Irom Sharmila reveals about the special man in her life

15-September-2011

Vol 2 | Issue 37

She is India’s best known face of peaceful protest. For almost 11 years, Manipur-based Irom Sharmila has been making daily demand for peace and withdrawal of the draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) from her state by being on a fast-unto-death until the Act is repealed.

Her struggle has earned her international recognition and admiration. Prestigious awards have come her way, including the Gwangju Prize for Human Rights in 2007. But her awe-inspiring determination has not moved the Indian government so far.

|

|

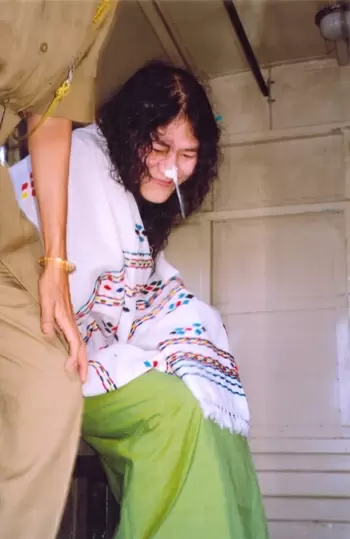

Silent determination: Irom Sharmila has been fasting since 2000 demanding withdrawal of the draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act (Photo: WFS)

|

The 12-day fast of anti-corruption crusader Anna Hazare has once again brought the spotlight on Sharmila. This has compelled the Central government to state that it is prepared to revisit the AFSPA issue and attempt a consensus to amend the law.

Sharmila has been described by a British newspaper as “the world’s longest running hunger striker”. All these years she has not even had a drop of water and cleans her teeth with cotton wool. In her home state the government’s response all along has been perfunctory. All that the state is doing is to keep her alive to discharge its constitutional obligation.

For refusing food and water, interpreted as a self destructive act, Sharmila has attracted charges under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code and s forced fed liquid diet by the hospital authorities through a nasal tube.

The maximum sentence for attempt to suicide is one year. In Sharmila’s case, the government keeps extending her remand, year after year, because she resumed fasting after being set free.

So her world today has been reduced to a special ward, measuring 12 feet by 10 feet, at Imphal’s Jawahalal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences. The ward is administered by the Sajiva Central Jail and Sharmila’s only outing is a fortnightly visit to the court of the Chief Judicial Magistrate for the extension of her judicial remand.

For companions, Sharmila only has her doctors, paramedics and security staff. Any communication addressed to her is first vetted by the authorities. Even her requests for a telephone call to family members are often denied.

This is the stifling and self forgetful existence that Shamila has chosen for herself to secure peace for the people of Manipur. When I met her recently outside the court of the Chief Judicial Magistrate of Imphal (East) she was clad in a green sarong with a white shawl draping her shoulders.

Escorted by a policewoman, she headed to the last bench in the courtroom and sat resting her right fist on the bench to prop up her body. Her face sometimes wore an expression of pain.

Her fasting has made her very sensitive to sunlight – it takes her a while to adjust to it. She is weak, pale and with thinning hair. But she is not complaining. She answered questions about her day-to-day life in a matter-of-fact manner, with no trace of self-pity, “I am a prisoner of conscience. I just think that it is my destiny to change society,” she says, adding with steely resolve, “I just see the goal and it is approaching. I know I will get success by being positive.”

Sharmila explains that she is content reading two Manipuri newspapers, the ‘Huyen’ and the ‘Lanpao’. She is not interested in television. She does yoga for about four hours every day because “it helps to balance my mind and body”. For the rest of the time she reads books.

The books have been sent to her mostly by her admirers, among who is someone very special. Sharmila says with a smile that lights up her face, “Most of the books come from the man I love. He is British and is now based in Nepal.”

His name is Desmond Cutinho, and she helps me with the correct spelling by writing his name in her shaky handwriting on my notepad. This May, Desmond had sent Sharmila a laptop, but she has been denied an Internet connection.

Asked if she has a message for UPA Chairperson Sonia Gandhi, the iron lady of Manipur replies, “I just want to tell Sonia Gandhi not to see us as step children. I want to remind her that she is also a woman and should try to understand the mind of a conscientious woman.”

Sharmila has reason to say this. Human rights activists point out that when Gandhi visited Manipur in 2010, neither she nor the Manipur chief minister met her.

When the time came to say goodbye, I, like innumerable others before me, pleaded with her to give up her fast. But she just smiled. She had to be helped to climb into the police van. The door then shut behind her and she was gone.

Perhaps what has kept Sharmila going is the support of her mother and elder brother, Irom Singhait. Looking back at the fateful events following the Malom massacre of November 2, 2000, in which 10 innocent civilians were mowed down by the Assam Rifles, Singhjit says, “It was a Thursday and Sharmila used to fast every Thursday.”

“She did not eat anything the following day either. On November 4, she went with some friends to a bakery in Imphal and had her favourite cake. The next day she went to a youth club building in Malom and announced her indefinite fast. She was arrested at 7.30 am on November 6 and charged under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code.”

“She was then taken to Sajiva Central Jail where she was administered a drip. Between November 11 and 21, the police brought Sharmila several times to our home with her release papers. They even beat up my brother. But the Meira Peibai (meaning torch bearers – a group of local women peace activists) formed a ring to shield him.”

Every Sunday, for five years now, Singhjit has been carrying a home-made hair wash solution known as csinghi, in a jug for Sharmila. Although he is 14 years older, he is very close to her. It is a bond dating back to her infancy.

It was he who had taken her as a baby to local women with newborns, who worked as wet nurses to ensure that she got her feeds, since her mother was unable to feed her. Today, he continues to worry, “I support her because I am convinced she has extraordinary will. But I am also terribly anxious. I have told her to continue as long as she has strength and I will support her.”

At her modest home in Kongkham Lieikai, Sharmila’s 78-year-old mother, Shakhi Devi greets us. She exhibits a resilience that reminds of her daughter. She has decided not to meet Sharmila as she fears it may weaken her resolve.

But she misses this youngest of her nine children deeply, and has even approached astrologers to find out if Sharmila would ever be set free. Some of them have predicted that a decision on the AFSPA will come from a “distant land.”

Sharmila’s protest has touched her family in innumerable ways. Singhjit has kept his promise to Sharmila by never seeking her release. He has even given up his government job to ensure that justice is done to her cause by actively working for ‘Just Peace’, an organisation founded by Sharmila with the cash component of her Gwangju award. - Women's Feature Service