Kashmiri women fight courageous personal battles overcoming disability

05-July-2013

Vol 4 | Issue 27

In the border village of Pukharni in the highly militarised Nowshera sector of Jammu and Kashmir, an eerie silence fills the air, punctured occasionally by the sound of cowbells, the chirping of birds and gunshots from the nearby firing range.

Under a clear sky, in the dusty courtyard of her mud house, Safia Begum, 35, is busy working in the kitchen. She kneads dough and then expertly makes rotis on an earthen ‘chulha’ (stove) – and she does it all, literally, single handedly. Safia lost her left hand to a landmine blast when she was just six.

|

|

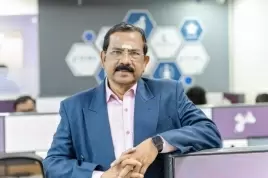

Many women have lost their limbs in landmine blasts in Kashmir. Fatima Jaan (above), a resident of Guntrian village, who lost her left leg in a blast, is seen with her son (Photo: Ashutosh SharmaWFS)

|

As she hurriedly finishes cooking, her sons, Baag Hussain and Yasar Irafat, who are in Class IV and III respectively, troop in. Back from a hectic day at school, her younger boy is tired, so Safia helps him change his clothes. Yasar too has lost his left hand while fiddling with a stray landmine in March 2011.

In the absence of any monetary relief from the government so far, this brave mother has courageously been struggling to raise her sons.

“Besides a little bit of farming, my husband and I do various menial jobs to sustain the family,” she says.

For Safia, educating her boys is her top priority. “Come what may, I won’t let my children’s education suffer. I have faced many hardships in life as I was illiterate and disabled. But my children study in a private school and I want them at least to have a dignified life,” she adds.

While Safia is being able to make ends meet, in Pukharni there are women like Naseem Akhtar, 23, and Sharifa Begum, 22, both of whom lost one of their legs as children in separate landmine blasts near their homes. They now stitch clothes for survival and are very worried about the future.

In the remote border regions of J&K, there are hundreds of women, who are not just victims of conflict but of official apathy and social indifference too.

For them, words like emancipation and empowerment hold little meaning. After being maimed or widowed or affected by conflict in some other unfortunate way, they have to battle on each day of their lives.

Rural folk largely depend on herding cattle and agriculture for their livelihood. Physically disabled persons can do neither. Imagine then their situation in the absence of any social protection or government support.

The reality is that a sizeable number of conflict-affected women, who cannot earn a livelihood through physical labour, have taken to begging on the streets.

Sitting near a sewage drain at the general bus stand in Poonch, Fatima Jaan, 40, is busy hammering nails into her dilapidated artificial leg with the help of a stone. After she is done, she swats off the flies buzzing around with her dupatta and the next moment raises her begging-bowl to passersby hoping they will drop a few coins into it.

Every morning this resident of Guntrian village, located near the Line of Control (LoC) in tehsil Haveli of Poonch district, hurriedly finishes the household chores, sends her three children off to school and then heads out towards Poonch town. She treks for nearly four kilometres and then boards a bus to reach her ‘workplace’, the general bus stand.

“A year after my husband disappeared, I started begging here. It has been 13 years now,” she states. With tears in her eyes she continues, “My husband, Noor Mohammad, went missing after he was taken by some Army personnel in 1998. No one ever saw or heard of him after that time.”

Fatima was grazing her cow near the house when she unknowingly stepped on a landmine. She lost her left leg in the blast. She does not recall the year of the incident but says with certainty that “it happened some years after my marriage”.

Then, as she looks at her amputated leg, she breaks down into loud sobs. Asked why she comes so far to beg and she replies, “If I beg in my area it is likely to bring disrepute to the family’s name. In a few years I will also have to arrange for the marriage of my daughters.”

Her case was taken up with the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) by a noted local activist, Kamaljeet Singh. Taking cognisance of her difficult situation, the SHRC in its final judgment of April 2011, recommended that the government provide suitable financial assistance to her without delay. This recommendation has not been followed up.

Gulkhar, another widow, is living with severe hardships. This mother of six daughters lost three buffaloes – the only family asset and source of income – when the cattle wandered over to a landmined pasture in a village near the LoC in the Bala Kote area of Poonch district last October.

“Despite reporting the matter to the local administration, I haven't got any relief yet,” complains Gulkhar, whose family ironically is categorised as Above Poverty Line (APL), as a result of which she does not get a widow’s pension.

Normally, widows get a monthly pension of Rs 200 whereas those who are above 64 years or fall in the Below Poverty Line (BPL) category are given a monthly pension of Rs 400 by the government.

“Most of our land is landmined; the rest is rocky and arid. Only a small portion is cultivable,” she says. These days, there is one question that keeps haunting her: “How will I marry my daughters? After losing our livestock we don’t have any source of income.”

Gulkhar also talks about Razia Bi, 65, and Sakina Bi, 65, who are her neighbours in the village. “Razia and Sakina lost their husbands to shelling from across the border. Neither of them received any financial assistance from the government. Their families are also facing severe economic hardships,” she reveals.

Innocent women and children, who have nothing to do with militancy in the state, have been suffering immensely just because they happen to be related to known militants.

Haseena Begum, a mother of a 12-year-old, is one such half-widow. Years ago her husband had reportedly joined the ranks of the militants and there has been no news of him ever since.

“I was 20 when I was married off by my parents. Two years later, my husband disappeared. My son was one year old at that time,” whispers a pale and tired Haseena, who has turned prematurely old and infirm by the age of 33 because of the daily deprivations that mark her life.

She lives in a small hut-like house with her only son on the periphery of the district headquarters of Doda, working in half a dozen houses as a domestic help to keep her home going.

“My parents have passed away now. Since the disappearance of my husband, I feel socially ostracised,” she reveals, stroking the head of her son sitting by her side even as tears roll down her sunken cheeks.

A few months ago, state Chief Minister Omar Abdullah had endorsed the recommendations given by the State Rehabilitation Council (SRC), which asked for assistance to be provided to all the women affected by the conflict.

Abdullah called for all concerned to contribute towards “formulating the operational module”. The recommendations, however, are yet to be translated into action.

Moreover, compensation to landmine victims, provided by the Ministry of Defence, is given only after the cases are processed on the recommendation of the District Development Commissioner. A disabled person normally gets a monthly pension of Rs 400 from the state’s social welfare department.

There are several ‘invisible’ women victims of conflict whose plight calls for an immediate humanitarian response. All they want is a better future for their children. Is that too much to hope for?

(The writer is a media fellow with the National Foundation for India, working in Jammu and Kashmir.) - Women's Feature Service