Electricity is a beginning in the uplift of villages and not the end

29-September-2012

Vol 3 | Issue 39

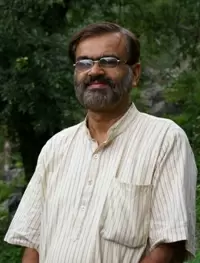

Why do villages need electricity? For household lighting, many would say. But Yogeshwar Kumar, an IIT-Delhi alumnus of 1974 batch, has set up environment friendly micro hydroelectric plants in the hilly regions of Uttarakhand, Kargil, Ladakh, Meghalaya and some parts of Orissa with a bigger vision.

He does not stop with supplying power to villages. He works through his NGO Jansamarth for development of the villages by using the electricity to set up small enterprises and creating jobs.

|

|

A village woman using a electric stove powered by hydroelectricity

|

In his three decades of service to rural people he has built 15 hydro-electric power stations which are manned and operated by villagers themselves, who use the power to run rural enterprises like atta-chakki (flour-mill), oil-mill, sawmill, and welding workshops.

Fresh out of IIT, this civil engineer preferred to first experiment with bamboo as a reinforcement material. Later, he became interested in hydro-electricity.

He made his first micro-hydel plant in 1975 on a stream to light up the incubators of a lab in Uttarakhand, where he was working with Professor Virendra Kumar of Zakir Hussain College (Delhi) in the field of Cytogenetics.

The power produced from the plant was put to several uses like oil extraction and wheat milling. They also built a school at Bhandar village for the village children who reared cattle during the day and attended classes in the night. The school was lit up using power from the hydel plant.

His second hydel-plant was in Dogri Kardi village. “We did power generation in small ways in many villages,” says Yogeshwar Kumar, who was also involved in the popular Chipko movement in the late seventies to protect the trees.

In the period 1984-1991, Kumar was in Meghalaya as special-officer-in-charge at the Government Science & Technology Department. He brought technology closer to the people and won their affection. His smokeless chulha became popular and was in great demand.

|

|

Yogeshwar Kumar

|

Though he has been working with government agencies, he says it is difficult to implement programmes when working with the government. For instance, though the government funds building of hydel-plants for remote villages in Leh, there is no allocation for repairs and maintenance.

“Villagers would ring me in Delhi from remote villages in Leh for repairs,” he says, adding that there is no skilled manpower in villages.He says there is imperative need to build strong cooperative units in villages and feels the government should lay emphasis on capacity building in rural areas.

Kumar built a 15 KW power station in Budha Kedarnath in Uttarakhand for an NGO ‘Lokjeevan Vikash Bharati’ in 1992-1993. A number of village enterprises were powered by the hydel-project.

In later projects, Kumar began to train the villagers in operation and maintenance of the power plant. Their wages were to be paid from income of the plant, which was collected from consumers as per their meter reading.

The small power stations set up by Kumar require falling water from an elevation to generate electricity. “In mountain areas there are many streams and rivulets but even in plains if water is made to fall through a pipe or tunnel from a height, one could generate electricity,” he says.

In 2009 Agunda village in Tehri district of Uttarakhand opted for a 40 KW micro-hydro power plant even though the village was going to be connected to the state grid.

The villagers wished to have their own plant, as it would be more reliable and any fault in the system could be repaired immediately – with their own trained manpower - unlike the government line that would take days to be restored in case of repairs.

|

|

A power station in Ladakh

|

Agunda is part of a Jansamarth-UNDP initiative in six remote villages of Tehri Garhwal to develop micro-hydel plants with the aim of providing livelihoods to villagers by using renewable energy and local resources.

“We are working in a holistic manner with community participation, training the villagers in maintaining the plant, and setting up processing units to encourage entrepreneurship,” says Kumar.

He said there was a big landslide in Agunda few years back. He argues that if villagers could use electricity for cooking, they need not walk daily 5 km for collecting firewood and it would also stop them from felling trees.

Kumar says using electric stove would cost a family roughly Rs 7 per day. “The villagers should slowly switch over to electricity for cooking food and save the forest. Still about 85 percent of our rural population use firewood for cooking,” he says.