Founder of Rs 800 crore steel conglomerate worked for Rs 5 at his father’s scrap yard

22-January-2020

Vol 11 | Issue 3

By the turn of this century, a little known brand called Amman TRY began to advertise in the Tamil print and television media with the tagline ‘asaikamudiyatha valimaikku Amman TRY murukku kambigal’ (For absolute strength, Amman TRY twisted bars) and started registering its presence in the market.

Back in those days, there were few players from Tamil Nadu manufacturing the twisted steel bars used in the construction industry, the bulk of which came from outside the state from companies like Vizag Steel (public sector) and Tata Steel (private sector).

|

|

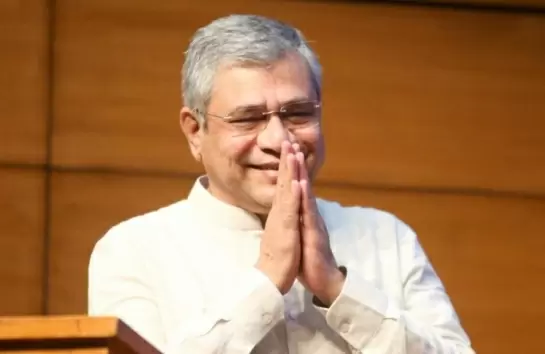

M Somasundaram, founder, Amman TRY Steel, cut his teeth in business at his father’s steel scrap yard as a teenager (Photos: Chidambaram)

|

Soon, the home grown brand became popular and behind the scene was expanding its operations under the leadership of a young founder M Somasundaram, a BBA graduate from National College, Trichy, who was also the copywriter and the creative brain behind the advertising campaign for Amman TRY then.

“In 2001 our production capacity was 1,000 tonnes per month. Now we produce one lakh tonne of steel bars of various sizes per annum,” says 44-year-old Somasundaram, founder of the Rs 800 crore turnover steel conglomerate, which traces its origin to a steel scrap business started by Somasundaram’s father S P Muthuramalingam in 1978 in Trichy.

I am at Amman TRY’s sprawling Fathima Nagar plant in Trichy, about 360 km from Chennai, and reliving the journey of this brand through the prism of its founder, who rarely gives interviews to the media, but has made an exception for us.

I am at Amman TRY’s sprawling Fathima Nagar plant in Trichy, about 360 km from Chennai, and reliving the journey of this brand through the prism of its founder, who rarely gives interviews to the media, but has made an exception for us.

“Amman is the name of our family deity and TRY is an abbreviation of Trichy,” he says, explaining how he came up with the brand name, which now has a presence across Tamil Nadu, in parts of Kerala and in Bengaluru, Karnataka.

“We have 12 per cent share of the TMT (Thermo Mechanically Treated) bars market in Tamil Nadu. We are not focusing much on other states at the moment due to logistical reasons,” he says. “Transporting materials from Trichy to faraway places will shoot up the cost of the product and make it unviable in a competitive market. We plan to set up production plants in other places besides Trichy and then focus on expanding the market.”

Somasundaram set up the first steel rolling mill in Nagamangalam, Trichy, at the age of 23, soon after his graduation, with no prior exposure of operating a steel plant, and with only some practical knowledge of the metal from his father’s scrap business.

“I understood the basic property of steel by experience and gained knowledge about the elements that constituted it, such as carbon, manganese, phosphorous, and sulphur,” he says. “I learned to segregate the different types of steel scrap and identify what kind of steel would go to a casting foundry and what type would go to a rolling mill or a melting unit.”

|

|

Amman TRY holds a share of 12 per cent of TMT bars market in Tamil Nadu

|

He would visit the steel plants clandestinely, accompanying the scrap laden trucks leaving their yard as a cleaner and taking mental notes of the operations at the factory. No wonder he loves calling himself as a ‘street-smart entrepreneur’.

Somasundaram saw his father’s scrap business grow from humble beginnings and remembers fondly the days when the family would go for a movie, once in six months or so, on a Lambretta scooter. His other childhood memory is of his father going on business trips to buy steel scrap and being away from home for 10-15 days at a stretch.

“He purchased the scrap from government enterprises like the Railways, BHEL (Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited), and NLC (Neyveli Lignite Corporation). He would then put the materials on a (railway) wagon to send them to the steel plants.

“It would take up to a week for him to arrange a wagon, so in that period he would sleep in the railway station till the consignment was dispatched,” says Somasundaram, narrating the family’s rags-to-riches journey, which he became a part of even at age 15. “My father was a motivated worker and he would work even on Sundays. He would not rest until at least two truckloads of scrap were dispatched from our premises daily.”

Somasundaram proudly shares that he would get his hands dirty as a teenager at the scrap yard helping his father, who had worked as an accountant cum purchase officer from 1971 to 1978 in a steel trading firm before setting up his own business.

|

|

Steel bars being made at the Fathima Nagar plant in Trichy

|

“On Sundays, there would be shortage of labour for loading the materials on the truck. I and my elder brother would happily fill in and do the job. Father would pay us Rs 5 for the day’s labour and it was big money for both of us,” he reminisces.

By the time he enrolled for his under-graduate degree at National College, Trichy, where he attended the evening classes, Somasundaram began to travel to different cities in Tamil Nadu, bidding at auctions to buy steel scrap.

“I might have been the youngest bidder around, with not even my moustache fully grown,” he chuckles, recounting his early days in the business, as he began to handle the banking work, prepare tenders and take part in auctions.

In an unforgettable incident while he was in college, Somasundaram had to rush to Erode after bagging a tender to take the mangled remains of 40 oil-laden wagons that had derailed at the Erode railway station. “It was a challenging job because the wagons contained oil and it was difficult to cut the wagons using gas and welding torches,” he says. “I and my team of workers worked day and night because the Railways wanted us to clear the wreckage within a week. It was a race against time and eventually we succeeded in meeting the deadline.”

They used to get several such railway contracts. “At that time metre gauge tracks were being replaced in Tamil Nadu with broad gauge tracks and we procured the discarded tracks in auctions,” he recalls. “I bid at the auctions. We would calculate the bidding price based on expenses we would incur in transporting the materials and I would stick to it. It is important to know when you have to stop bidding and back off at auctions.”

|

|

Somasundaram set up a billet plant at Naidupet, Andhra Pradesh,in 2011

|

These nuggets of insight he imbibed from his father, his passion for business and the quest to constantly push the boundaries, saw him emerging from his father’s shadow in 1999 to set up his own steel rolling mill at a cost of Rs 1.5 crore – with self-funding of Rs 50 lakh, and debt funding of Rs one crore.

The plant produced cold twisted deformed (CTD) bars. The takeoff was not smooth though. In about five months the rolling mill ran into losses. “We lost about Rs 25 lakh. I was shattered to see the hard earned money of our family going up in smoke,” says Somasundaram. “I thought of stopping the work, but gave up the idea since around 100 employees would lose their jobs.”

Instead, he reviewed the entire production process since inception minutely and found that the quality of raw materials (ingots) was not good and it led to a lot of wastage causing huge losses.

To get the company back on track again, he needed fresh funds. He approached a private financier and got a loan of Rs 40 lakh. “I took a big risk, but managed to clear the mess in a very short time and made the company profitable,” he says. To improve product quality and reduce wastage, he procured billets from Vizag Steel Plant, and within two months the situation began to change.

“We got a repeat order from a dealer in Nagercoil and it made my day,” he recalls. It was the time when he was going around on his ambassador (non-AC) car canvassing for orders from dealers and the order came as a whiff of fresh air.

“I was so excited that I took the train to Nagercoil and I was at their shop next day morning at 9.30 am just as they were opening. I wanted to find out from the owner why he chose our brand,” he says. The answer he received opened his eyes to a great marketing strategy that he would implement across the state quite successfully.

|

|

Throughout his career, Somasundaram has worked closely with the working class

|

“The owner said some bar benders (in the construction work) had requested for our brand as they felt it was both strong and flexible,” says Somasundaram, who understood at that point of time the power of ordinary workers in promoting his brand.

This incident sparked the birth of Amman TRY’s remarkable initiative to reach out to bar-benders and workers in the construction industry across the state. Somasundaram visited the small towns and cities of Tamil Nadu, and with the help of local dealers connected with thousands of bar benders at meetings held in wedding halls on a weekly basis.

“Around 300 to 1,000 people would attend a single meeting. I did about 400 to 500 meetings in a span of 10 years and the bar benders became our brand ambassadors,” he says.

The brand grew overcoming many challenges. In the early years, Amman TRY was denied TOR 40 grade, which was an important selling point for steel bar manufacturers. Somasundaram suspects the hand of vested interests in stalling the TOR 40 certification for Amman TRY.

It was a major setback for the fledgling brand at a time when all the competitors flaunted TOR 40 as a hallmark of quality. Many would have lost their nerve in such a situation, but not Somasundaram who quickly got BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards) certification and promoted the BIS specified FE415 grade on Amman TRY steel bars.

|

|

When pushed to a corner, Somasundaram always fights back with renewed vigour

|

“A true entrepreneur never gives up,” he says. “I could have got stuck up if I had become obsessed with TOR 40, but I looked for alternatives and FE415 grade came to my rescue. Initially, it didn’t resonate with the people, but soon the whole industry began to seek FE415 grade as it was made mandatory and TOR 40 faded out.” The TOR 40 episode brought out his street-smart approach to the fore, which bailed the company from a crisis that threatened to finish the brand.

As business grew, Somasundaram focused on developing the infrastructure to increase production. In 2004, he set up a billet plant at Karaikal in Puducherry, and then installed a 1250 KW wind power plant at Radhapuram in Tirunelveli district. The plant now supplies about 20 lakh units of power per annum to the TNEB (Tamil Nadu Electricity Board) grid, which contributes to an annual saving of Rs 1 crore on their electricity bill.

A second rolling mill was established in Trichy in 2006. In 2011, the company’s turnover touched Rs 350 crore and he established a massive Rs 100 crore integrated billet plant at Naidupet in Nellore district of Andhra Pradesh. The plant was set up at Naidupet due to its geographical proximity to the Bellary iron ore region in Karnataka and the ports of Krishnampet (40 Km) and Chennai (80 km).

|

|

Wife Vanitha has been a constant companion for Somasundaram in both his business and personal life

|

Somasundaram is passionate about giving back to the society. “We extend educational assistance every year to about 500 poor students ,and provide roads and drinking water facilities in villages,” he shares.

He is out of town at least two days in a week and loves to play shuttle with his friends in the morning whenever he is in Trichy. His elder son Sharan is doing his second year BE (metallurgy) at a college in Coimbatore and the younger son, Yashwanth is studying in Class 10.

His wife S Vanitha is involved in office administration and regularly interacts with the marketing team to develop the business. The couple has fine chemistry and speak highly of each other. Vanitha says she has one wish though, which is to take a spin with her husband on his new Jawa. This, no doubt, should be music to the ears of her doting husband, who is used to responding to much tougher challenges in his daily grind.

This Article is Part of the 'Amazing Entrepreneurs' Series