A remote village in the Sunderbans gets solar power due to efforts of local women

13-August-2016

Vol 7 | Issue 33

Darkness is generally associated with gloom, desperation, anxiety, fear… all of which, until not so long ago, were a part of the everyday lives of the families living in the small, remote hamlet of Sardar Para in Satjeliya Island.

Minati Aulia still remembers the day her neighbour Bula lost her husband, a fisherman, because of the all pervading darkness that used to engulf the area after sundown. “One evening, he was returning from the riverside after work when a tiger came out of nowhere and dragged him away. He couldn’t be saved because it was just too dark to see anything,” she recalls.

|

|

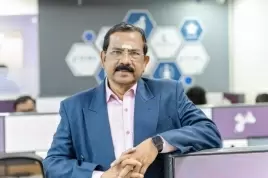

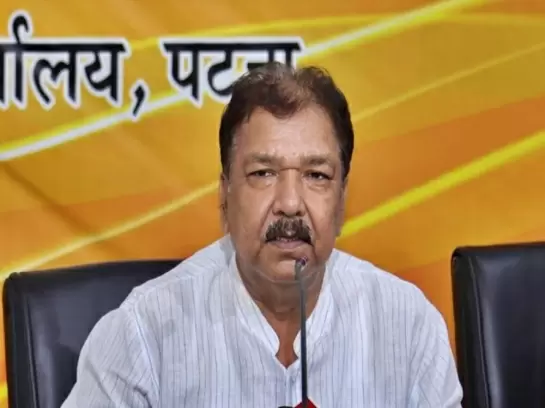

Residents of Sardar Para in Satjeliya Island were put to a lot of hardship in the absence of lighting after nightfall, but the installation of solar panels have changed their lives for the better (Photo: WWF)

|

Over the years, Minati has seen many families lose their loved ones to incidents like these. She remembers how everyone used to be desperate to get an early start to their day because there was no way anyone could hope to do anything once dusk fell.

The men had to leave the fields for the fear of being attacked by a tiger coming from the Sajnekhali Wildlife Sanctuary in the vicinity, women were compelled to wrap up their household chores and the children were unable to do any schoolwork because how much reading and writing could one do by the faint light of an oil lamp.

Surrounded by the dense mangrove forests of the Sunderbans, this village of around 100 homes is not the easiest of places to live in especially because not only is there a looming threat of cyclonic storms in the region but it is also virtually cut off from the mainstream.

Incidentally, it takes a bus, boat and rickshaw ride from the nearest town of Canning in South 24 Parganas district to get to Sardar Para. Yet, fortunately for the largely tribal inhabitants of this hamlet their womenfolk have diligently worked together to bring light and, consequently, much-needed change to their dreary existence though solar power.

Four years back, when the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) came to the community with a proposal to electrify the village with solar power, a clean, renewable source of energy, individual families were not too enthused at the prospect of having large solar panels dominating the rooftop of their house.

What if the panels got damaged in the frequent storms? What about the cost of maintenance? For people who were already existing hand-to-mouth absorbing an additional expenditure was simply not an option.

When it looked like things were going south, it was the local women, as part of the Sardar Para Paniyajal Samiti, who stepped in and decided to take matters into their own hands. They clearly understood the benefits of having regular electricity in their area and were ready to brainstorm with the experts to come up with a viable plan.

With cooperation of the committed self help group (SHG) women, a workable solution was in place real soon: by mutual consent it was decided that instead of asking standalone families to mount a photovoltaic panel at home a central charging station would be set up for everyone’s convenience. At the same time, each household would be provided with a battery-powered energy access kit, which could be charged at this station when it was low on power.

Today, the large shed that serves as the “power station” of Sardar Para is the most prominent structure in the village. It produces and stores about 4.1kwp of electricity every day, which is adequate to meet the energy requirements of all the residents.

The distribution module is straightforward: for a monthly fee of Rs 110 villagers can come to the charging station to charge the batteries that come with the energy access kit. The SHG women are responsible for collecting this modest charge as well as the maintenance of this nodal facility.

“It basically works like the inverter in our homes. The batteries power the lights and fans and once they get exhausted they are brought over to the charging station,” informs Soma Saha, Associate Landscape Manager, WWF-Sundarbans. On full capacity, the rechargeable batteries can power two bulbs of 100 watt each and a fan for up to three to four days.

The monthly payment allows families to gain access to the facility 10 times and the amount that is collected is duly deposited in the bank so that there is a ready corpus for them to tap into whenever they need to buy new batteries; each battery lasts for around five years.

“It was our SHG that convinced the larger community to back this project and even donate the land where the charging station has been built. Nowadays, we monitor its upkeep and the members are also in-charge of ensuring that the street lights throughout the village are in working order,” shares Minati, the proud leader of the Sardar Para Paniyajal Samiti.

Thus far, conventional electricity hasn’t reached the people of the delta islands, which are threatened by climate change and rising sea levels. Which is why Sardar Para’s successful, and now sustainable, experiment has become a model of sorts.

“This is a clean energy source that has had a revolutionising impact on their lives. Significantly, it has opened up new avenues of livelihood for them, which has, in turn, cut down their dependence on the forest and reduced the man-wildlife conflict in this zone,” explains Ratul Saha, Scientific Officer for Landscapes, WWF-Sundarbans.

He adds that though the WWF primarily works on wildlife and environment protection such initiatives don’t just fulfil their conservation mandate but provide a new lease of life to the otherwise reclusive communities living on the margins.

It’s truly been a dramatic transformation for Sardar Para. As evening sets in, the street lights come to life as do the bulbs in homes and there is a constant buzz of activities till late. In fact, several local enterprises - tea and snack stalls and quaint stores stay open way after sundown.

Women, in particular, have been able to pace their chores – for instance, many go to fetch water from the nearby tubewell after sundown as they no longer fear animal attacks – and take out more time to chip in with some extra income generating work.

For Minati and others, who used to solely depend on crab seed collection to augment their family earnings, the options have certainly expanded. Basanti Mondal, who was attacked by a crocodile once as she was collecting crab seeds at twilight, no longer needs to go to the riverfront she so dreads.

“Thanks to the solar lighting I can make better use of my time doing handicraft, which we sell in the market in town,” she says, showing off the skilful embroidery she has done on pillow covers and bedsheets with great satisfaction. “It took me a while but I’m not scared of venturing out at night anymore,” she adds.

For children the uninterrupted power supply has translated into an opportunity to catch up on their lessons as well as their favourite television shows. Sorobhi, 14, speaks for her lot when she says with a wide smile, “One finally feels connected to the rest of the world. We can lead a normal life and, what’s best is that I get to watch TV whenever I am free!”

Indeed, for the hardworking residents of Sardar Para, many of whom worship the sun god, their heartfelt prayers seem to have finally been answered. - Women's Feature Service